This year has been filled with big international stories so far. From the nuclear deal with Iran to the protests in Venezuela there have been a variety of stories that has been caught the attention of many across the globe. Ukraine’s political upheaval and the subsequent Russian annexation of Crimea has received possibly the most hyperbolic coverage out of any event. With the Foreign Secretary of the UK calling the Crimean annexation “the biggest crisis in Europe in the 21st century” and various pundits drawing comparisons to the German invasion of Sudetenland 1938, one might suspect that leaders in the West are preparing for war. Instead the United States and European allies have passed a series of mostly symbolic sanctions, such as suspending Russia from the G8.

It is striking how quickly things have developed in the crisis. On November 21st, when Ukraine’s then president Viktor Yanukovych abandoned an Association Agreement with the European Union to seek better ties with Moscow he could not have predicted how quickly the backlash against his government would come to bear. This was in part because of the protestors desire for the country to be closer with Europe but also a reaction to the government’s violent crackdown on protesters. By the end of February Yanukovych had fled the country a coalition of opposition members and Maidan-affiliated politicians formed an interim government. During this time unmarked gunmen took control of several government buildings in Crimea, flying Russian flags at some. The Parliament of Crimea replaced the sitting Prime Minister of Crimea with pro-Moscow Sergey Aksyonov; who, among other things, is nicknamed “Goblin” and has a disputed history with organized crime. On March 11 the Crimean Parliament declared independence from Ukraine and agreed to hold a referendum on joining the Russian Federation. By mid-March Russian forces had taken control of most institutions and helped administer the referendum, which allegedly passed with 97% support. Eventually the last remaining Ukrainian troops agreed to surrender, making it unlikely that Crimea will ever be part of Ukraine again. The crisis has not ended there: Russia has massed troops on its border with Ukraine and pro-Russian militants have taken control of several Eastern Ukrainian towns and cities.

Something that makes the sudden developments in Ukraine so striking is that I can recall very well what the sentiment was like six years ago when Russia invaded parts of Georgia. Then, like now, many pundits and foreign ministers denounced the move, but most of them seemed to think that the special circumstances in that conflict were unique and there was little risk of Russia repeated the move in Crimea. “Georgia is a small country, Ukraine is much larger and better armed” was often repeated; surely the West would not allow Russia to annex part of a country of 44 million seeking to join Western institutions like NATO and the EU. My point is not to mock the incorrect predictions made by people six years ago but instead to point out the unpredictable nature of international affairs. Instead of making bold prognostications I would like to discuss some of the possible longer term outcomes in the region and across the world.

The first potential implication I’d like to mention is a theoretical one: the undermining of the so-called “international order.” Among the terms that have been used repeatedly without definition has been the “international order” that Russia is supposedly undermining. I would like to explain what this term means before speaking to the effect Russia’s actions have had on it. Most pundits use international order as shorthand for a number of institutions and processes that exist to enforce international law; chief among these is the United Nations General Assembly and the UN Security Council. Not only has Russia ignored the very long held norm of respecting territorial sovereignty, but it has specifically violated a treaty which it signed with Ukraine agreeing to do so (the 1994 Budapest Memorandum). Vladimir Putin has tried to defend its actions on humanitarian grounds, saying that ethnic Russians are vulnerable to “fascist” Ukrainians whom he alleges control Kiev. They also allege that most Crimeans would support Russian annexation, but ignore the misgivings of the local Ukrainian and Tatar population. Most of Russia’s allegations remain hard to prove or are disputed by other foreign offices, Russia has been thoroughly isolated at both the UN General Assembly and the UN Security Council in recent votes.

Perhaps the biggest elephant in the room when US Secretary of State John Kerry accuses Russia of undermining the international order has been America’s own foreign policy since 2003. Prior to the invasion in Iraq the Bush administration was unable to secure the support of not only Russia or China on the UN Security Council, but also France. This made a vote meaningless, and made another NATO operation a non-starter, as France and Germany were opposed to any action in Iraq. By circumventing the institutions that uphold international law and ignoring the norms that underpin international order, the United States damaged its own claim as an upholder of the international order. This does not, however, justify Russia’s actions in itself and it’s worth noting that the Obama administration has placed much emphasis on using international organizations as vehicles of its foreign policy. Right now Crimea looks like a lost cause for Ukraine and the West, but there are other outcomes that should be mentioned both with Ukraine and the wider region in mind.

Ukraine’s connection to the Russian state and Russian history cannot be understated. The modern Russian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian ethnicities all trace their ancestry to the Kievan Rus‘ which was governed by Vladimir the Great (a Swedish Viking who converted a Slavic kingdom to Orthodox Christianity when he was baptized by the Byzantine Empire). Ukraine’s modern history is similarly tied to Russia’s; as part of the Russian Empire, Ukraine became part of the Soviet Union and experienced a massive terror-famine in 1932-3. With the fall of the Soviet Union political borders were created that did not necessarily match ethnic ones: millions of ethnic Russians reside in nations outside of the Russian Federation.

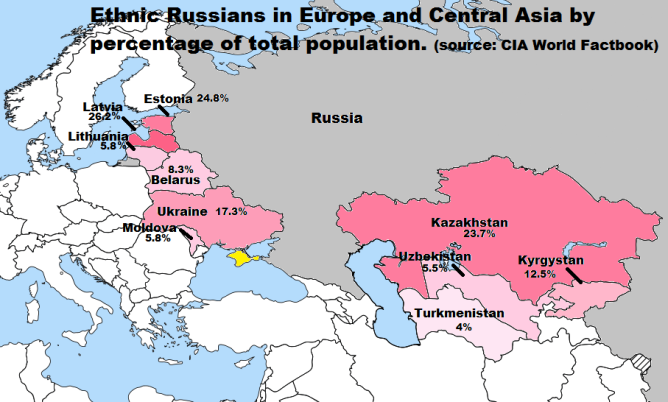

Before annexing Crimea, Putin said in a speech that he reserved the right to protect ethnic Russians living outside of Russia; as one can see with the map above, Ukraine is not the only country with a large ethnic Russian population. The dissolution of the Soviet Union left large ethnic Russian communities in countries whose post-independence foreign policy has sometimes been at odds with the Russian Federation. Perhaps the best examples of this has been the so-called Baltic states: Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania. All three states are members of both the European Union and NATO, and all retain a large ethnic Russian population (Latvia and Estonia in particular). This had lead to ethnic tensions in these countries after the Russian takeover of Crimea. But the Baltic states have certain advantages that Ukraine lacked when Crimea was invaded by Russia. Being members of NATO, all member states are obliged to treat an attack on one as an attack on all, with Article 5 of the treaty. This collective security guarantee makes it unlikely that Russia would consider threatening the Baltic states with military invasion. Non-NATO countries with Russian populations face a less clear future.P

Moldova, with its own ethnic Russian breakaway province (Transnistria), lacks any such agreement with the West and there have been fears that a renewed offensive by Russia could cross through southern Ukraine all the way into this breakaway province. Central Asia was also part of the Soviet Union and possesses its own large ethnic Russian population. In Kazakhstan nearly a quarter of the population is ethnically Russian and Russian is the language of business there. This connection, along with shared Soviet history, has resulted in a deep bilateral relationship between Kazakhstan and Russia. Kazakhstan along with Belarus and Russia are the only current members of the Eurasian Customs Union that Ukraine’s former president tried to join in place of a European Association Agreement. Despite these close relations, there has been some ambivalence in Kazakhstan about the Russian annexation of Crimea. This has been underscored by the decision to suspend Russian missile testing in Kazakhstan after an accident in Western Kazakhstan. While the suspension of testing occurred in response to the missile accident, Russia’s decision to place missiles near its border with Kazakhstan has been called a “Russian show of force” by some analysts there. Russia claims that the border missiles are there to protect Kazakhstan from “external threats” in Central Asia, but there are critics in Kazakhstan who view the military buildup as part of an “imperial policy” by Russia. The long term consequences of Putin’s pledge to protect Russians living abroad will have a varied effect from Kazakhstan to Estonia. I believe that the most important factor in Russia’s relationship with its neighbors won’t be the proportion of Russians living there, but the geopolitical orientation and treaties those countries are party to.

Russia’s annexation of Crimea underscores the increasingly geopolitical lense with which the Kremlin views domestic politics in Ukraine; these views have been reinforced by a historical sense of injustice. In Putin’s speech, he not only vowed to defend ethnic Russians living abroad, but also decried a quarter-century of “injustice” by the West. Specifically, he accused the West of expanding NATO to Russia’s border without consulting it, saying: “with the deployment of military infrastructure at our borders. They always told us the same thing: ‘Well, this doesn’t involve you.’ ” I emphasized the latter part of the quote because I think it underscores just how differently the Kremlin views the post-Soviet order from the West. While the West views former Warsaw Pact states and Soviet Republics joining organizations like the EU and NATO as a free choice made by democracies, the Kremlin sees a plot to undermine Russia. In light of this it is unsurprising that Putin viewed the Maidan protests as a Western plot to remove Ukraine from his “sphere of influence.” These divergent interpretations of events in Ukraine and other neighboring countries are at the heart of why Russia and the West struggle to understand each other’s intentions.

To be frank, I believe that Russia’s geopolitical approach to events in neighboring countries underscores the very weakest points of Realist theory in international relations. To briefly summarize this school of thought, Realists believe that international relations are dictated by an anarchic system of nation-states where power politics determine relationships. When Yanukovych declined to take steps to join NATO and later to sign an Association Agreement with the EU, the West accepted it not because it didn’t value Ukraine’s participation, but because the West viewed Ukraine’s domestic politics as the crucial determinant of any treaty. By ignoring this, or viewing it cynically, the Kremlin has alienated a large number of Ukrainians or other neighboring countries who may have otherwise supported close relations with Russia: domestic politics matter in international politics. Secondly, Russia’s realist/geopolitical take on the Association Agreement with the EU ignores the true appeal of the EU and NATO: these institutions are governed by the rule of law and offer meaningful incentives to members. The EU offers access to a massive single market and the promise of modernizing the economy of a country; one only has to look at the difference in economies of Ukraine and Poland since 1990 (graph below). NATO, with its Article 5 guarantee is possibly the golden standard of collective security; it is also a democratic institution, with core members often refusing to participate in the military adventures of others. Russia’s alternative alliance (the proposed Eurasian Economic Union) is both economically weak and imposes many costs on its members in addition to some benefits: the Eurasian Economic Union is no rival the European Union.

(Source)

Some pundits have speculated that the continuing crisis in Ukraine and annexation of Crimea could lead to a new Cold War between Russia and the West. There are a variety of reasons why I don’t believe that this will take place. The Russian Federation has a population that is 1/3 the size of the United States and an economy that is 1/8 the size in nominal terms; the Soviet Union had a larger population than the US and an economy about half the size in 1989. Russia is no longer part of a broader military alliance like the Warsaw Pact during the Cold War, and while the Shanghai Cooperation Organization has been muted as a rival to NATO, it lacks any treaty obligation on its’ members collective security. And unlike during the Cold War, there aren’t two rival ideologies that are being promoted by great powers; the Kremlin’s “model” has hardly proven itself within Russia. This is not to say that Russia is incapable of imposing costs on the West, Europe’s dependence on Russian gas and oil gives it potent leverage over the continent. Even the proposed export of US liquified natural gas to Europe couldn’t begin to supplant Russian gas, a fact not lost on the Russian government. But even if the West is limited in its ability to sanction Russia, negative sentiment in the markets could hurt its economy, possibly causing a recession. It is because of these realities that I do not expect there to be a greater escalation of conflict between the West and the Russian Federation, but instead think that relations between the two will enter a “new phase.”

All of the potential outcomes I’ve mentioned so far are, at their heart, speculations on my part; with that said, I believe I have defended my predictions well. Russia’s annexation of Crimea will undermine the international order, but that order was already weakened by the US invasion of Iraq. While Putin’s irredentist pledge to defend ethnic Russians abroad has worried neighboring countries with large Russian populations, many of these states are already members of the EU and NATO, making military action more costly to Russia. The few countries (Ukraine, Moldova) that aren’t members of either treaty are, however, at risk of facing economic/military pressure from the Kremlin. The risk of the crisis escalating into a new Cold War between Russia and the West seems unlikely for a variety of reasons including the weakness of Russia’s economy and Europe’s dependence on Russian petroleum. What is less certain right now is how events will unfold in Ukraine. As I write this blog pro-Russian militants have seized control of several towns and cities in Eastern Ukraine. How the government in Kiev responds to this will have a greater effect on the future of Ukraine than any power politics by Russia or the West.